The Golden Age of Wall Street: Part I

by

Ross M. Miller

Miller Risk Advisors

www.millerrisk.com

July 12, 2004

If you walked to just the right spot on Morris Avenue—maybe a hundred yards past where the man in the broken-down bus

used to sell hot donuts for five cents each to the kids in the

neighborhood until the health department got wise to him—you could see

the two towers rising in the distance. Morris Avenue began at the

Elizabeth train station and headed so far into the heart of New Jersey

that it seemed to me like it went on forever.

For two summers, I took the train from Elizabeth into

Newark's Penn Station and then caught the PATH train into the temporary

World Trade Center (WTC) stop. Only one WTC tower was open when I started

work on Monday, June 21, 1971 and the concourse in which the

"permanent" station would reside would not be built for years.

Indeed, it was watching the PATH trains coming into the current makeshift

station at Ground Zero on a recent visit to a friend whose new office

overlooks the site (and whose old office was in it) that got me thinking

about the old days.

I worked on the 11th floor of 11 Broadway, across from Bowling

Green Park, a verdant sliver that fronted the Customs House. It was

typical of many of the older buildings in the Wall Street area and it is

still standing. It was good that the walk from the PATH station to the

office was downhill because I would not discover coffee for three years—the closest that I came to coffee during the twice-daily coffee

breaks were the Drake's coffee cakes to which I had become mildly

addicted. I have the distinct impression that they tasted better back

then.

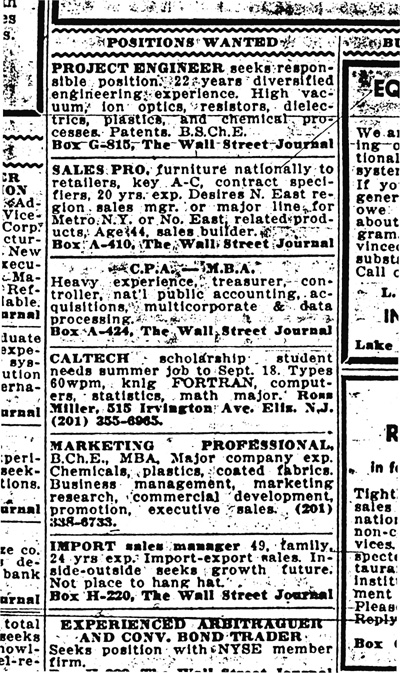

One might say that my mother got me this job. She placed

a classified ad on my behalf that appeared on page 22 in the June 15, 1971

issue of the Wall Street Journal. The ad, which appears among the

ads below, is largely truthful. I was not yet a Caltech student (I would

start my freshman year in September) and my mother must have estimated my

typing speed using a form of nonparametric statistics that I have yet to

reconstruct.

I remember only a single call in response to the ad (I think that there

may even been one or two others) and that was from a company called the

Graphic Scanning Corporation. I went in for an interview, passed their

typing test, and was hired on the spot. I cut my final week of high school

classes and was fortunate that both class day and graduation were held in

the evening. My hourly pay was $1.75, a stunning fifteen cents more than

the minimum wage.

Although Graphic Scanning was not an investment bank or

brokerage house, it was very much at the center of what was happening on

Wall Street in the days leading up to the Dow's first breach of 1000 in

late 1972. Graphic Scanning handled virtually all of the communications

involved with public offerings—both initial and secondary. The

"tombstones" for these offerings took up a good chunk of the

real estate in a thirty-two page issue of the Wall Street Journal.

Graphic Scanning sent out all the paperwork associated with the offerings

and received all the confirmations from syndicate members that they had

sold their allotted shares. Traditionally, this business had gone to

Western Union, but through specialization, Graphic Scanning could provide

faster and better service than WU and undercut their prices.

The heart of Graphic Scanning was a room roughly

ten-by-fifteen feet that held dozens of that marvel of modern technology—the "graphic scanner"—known back then as the

facsimile machine and now just the fax machine. They were slow—a single

page dense with text took several minutes to transmit—but they were

effective when they weren't being repaired, which was often. I had never

seen a fax machine before and would not see another one for several years

after I stopped working at Graphic Scanning. Caltech, which had every

high-tech toy imaginable, did not have fax machines around where students

could see them.

It should be noted that back in the early 1970s, very

few college students had summer jobs on Wall Street. The only ones that I

had every heard of were my colleagues at Graphic Scanning. Even my Harvard

contemporary, Bill Gates, with all his connections couldn't swing a summer

job on Wall Street (not that he even thought of trying). Bill's mother may

have had clout, mine had chutzpah). Understandably or not, Wall Street

firms were reluctant to hire "smart" college kids, much less let

them near their computers. Anyway, with one or two exceptions, brokers and

investment bankers used computers to send out statements, not to make

investment decisions.

Graphic Scanning was the brainchild of Barry Yampol. The

company was essentially a cream-skimming operation. Barry would find a

profitable segment of the telecommunications business and go after it. His

initial thrust was to take away Western Union's Wall Street business and

he would go on to become a pioneer in the cell phone industry. My

coworkers told me that his previous venture was a company that made socks.

In later years, I would meet several people who were

just like Barry—all of them hedge fund managers. Barry appeared to live

at the office along with his wife (who did things like manage the payroll)

and his son. Barry also "adopted" the other college student who

was working at the company when I arrived. He was a Reed College math

student and I have forgotten his name, so I'll call him "Barry

Jr." Both Barry and Barry Jr. were short and ambitious. I was tall

and a bit of a slacker back then even though the word had not yet been

invented.

Graphic Scanning had a caste structure. The lowest class

was the messenger class. The messengers, many of them my age but not my

ethnicity, hung out in a holding room and would smoke pot in the men's

room. The office manager was a crusty ex-Marine named Nat. (I think of his

last name as being Hentoff, but that's someone else). Nat biggest job was

to keep the messengers in line. The fistfights that frequently broke out

between Nat and the messengers provided entertainment to the other

workers. Messenger turnover was high.

On the next rung up the ladder were the guys in the fax

room who looked like older security guards who had been fired for

inattentiveness. They would spend day and night wrapping one page after

another around each fax machine's drum. These guys were human page

feeders.

Above the fax guys were the phone girls. They came from

Brooklyn and Queens and were not yet old enough to be "old

maids," a term that the incipient feminism of the time had not erased

from the language. They would write each message on a sheet of paper. The

typical message was: "To Drexel Firestone. WAAS 500 NSM. White,

Weld." Our phone gals knew all the brokerage guys calling in with the

messages and I was under the impression that some primitive form of phone

sex was going on. Developing a good relationship with customers is

important to a growing business.

The next class up was where I started out. As a message

typist. We took what the phone gals scribbled down and turned it into

presentable messages. For example, "WAAS" meant "We are all

sold" and there were other standard abbreviations. The typists were

more skilled (or less skilled, depending on how you look at it) versions

of the phone girls along with a smattering of college kids like me.

The key to being a fast and efficient typist was not raw

typing speed, but a good memory. The more addresses you could memorize,

the fewer that you had to look up. (The phone girls never wrote down the

address unless it was from an irregular syndicate member.) My favorite

brokerage name was "duPont Glore Forgan" for which I coined the

phrase "the average forgan has three legs and harbles." (The

etymology of the word "harbles" can be traced back to a coinage

of the "Podmind," an actual Southern Californian cited in Rigged.

Further details will have to wait until my Caltech memoirs.) Financial

regulations, scandals, etc., eliminated most of the firms that I

memorized. Back then, there were two Huttons—E.F. and W.E.—now there are

none.

The more complicated typing tasks, including the full

text of securities offerings, belonged to the next class up. They

consisted entirely of message typists who hung on long enough without

being fired. While I was there, long enough was about six weeks.

All of these castes worked in Graphic Scanning's back

office. In the front office, the two highest castes resided. The lower of

the two did "special projects." Barry Jr. worked there until he

was fired and I would work there during my second summer at Graphic

Scanning. The highest caste was Graphic Scanning's executives with the

exception of Barry, who was a caste unto himself.

With all this background out the way, I can start

getting down to real business next week.

Copyright 2004 by Miller Risk Advisors. Permission

granted to forward by electronic means and to excerpt or broadcast 250

words or less provided a citation is made to www.millerrisk.com.